Low Water on the Mississippi Slows Critical Freight Flows

Data spotlights represent data and statistics from a specific period of time, and do not reflect ongoing data collection. As individual spotlights are static stories, they are not subject to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS) web standards and may not be updated after their publication date. Please contact BTS to request updated information.

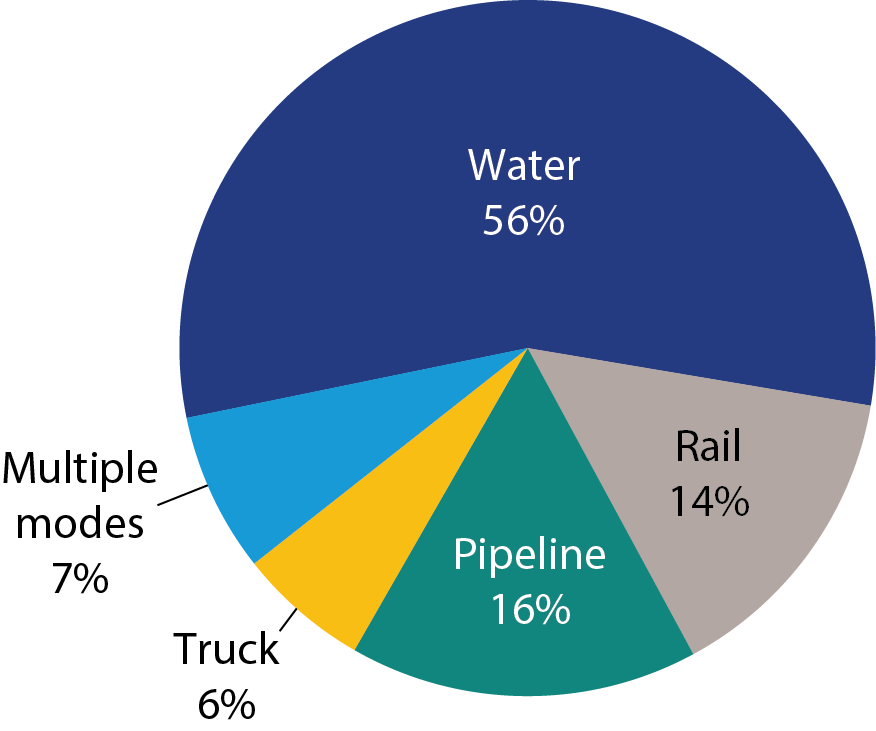

The Mississippi River provides a vital link for freight movement in the United States. In 2020, the river carried more than half of the 165.5 million tons that moved between the 12 states touching the Upper Mississippi System (1) and Louisiana (figure 1). The percentage of freight carried by the river to Louisiana is much higher for some states: 92 percent for Indiana, 81 percent for Missouri, 80 percent for Illinois, and 75 percent for Kentucky. Today, that flow of freight has been hampered by low water levels on the Lower River.

Figure 1: Percent Tonnage by Mode between States on the Upper Mississippi River System and Louisiana.

Much of Illinois agricultural product travels to Louisiana’s ports by river.

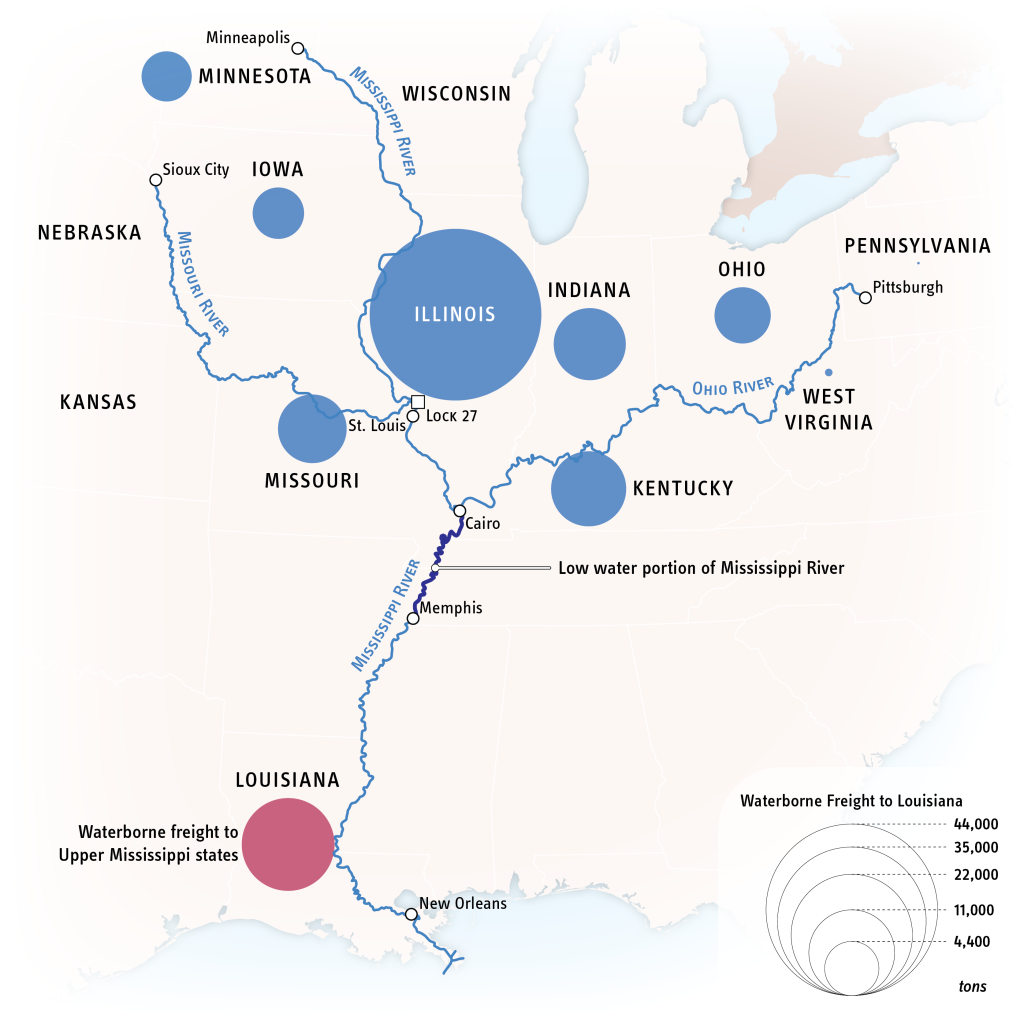

Of the 12 states, Illinois shipped the most freight to Louisiana in total (55 million tons) and by water (44 million tons) in 2020 (figure 2). Cereal grain accounted for 43 percent of the total tonnage between Illinois and Louisiana, and other agricultural products accounted for 26 percent. The river carried 93 percent of the cereal grain between Illinois and Louisiana, compared to 6 percent by rail, and it carried 82 percent of “other agricultural products” (2) between those two states, compared to 15 percent by rail and 3 percent by truck.

Figure 2: Waterborne Tonnage between States on the Upper Mississippi River System and Louisiana.

These statistics are from the most recent annual estimates in version 5.4 of the Freight Analysis Framework (FAF) available at www.bts.gov/faf.

Water level on the Lower River constrains downbound and upbound freight movement.

Our ability to move freight on the Mississippi River depends on water levels, whether too much due to flooding or too little due to drought. Currently, low water levels in the Lower Mississippi River due to scant rainfall have severely hampered fall 2022 barge shipments, especially on the vital stretch between Cairo, Illinois, and Memphis, Tennessee (figure 2). Groundings and the need for dredging have closed sections of the river and halted barge movements for intermittent periods. U.S. Coast Guard District 8 (New Orleans) reported a backup of more than 2,000 barges on the Lower Mississippi in early October. Low water also restricts the loads each barge can carry, and the narrower channel restricts the number of barges in a single tow.

Rain from Hurricane Roselyn eased the problem slightly in late October, but long-term weather forecasts do not anticipate enough rain to restore full river operations for at least several months.

Rail shipment is the normal alternative to barges, but our rail system can have difficulty absorbing such a massive short-term shift. Moreover, concerns over a possible rail strike in 2022 have made shippers hesitant to rely on a rail option.

Shipment of seasonal products cannot afford to wait.

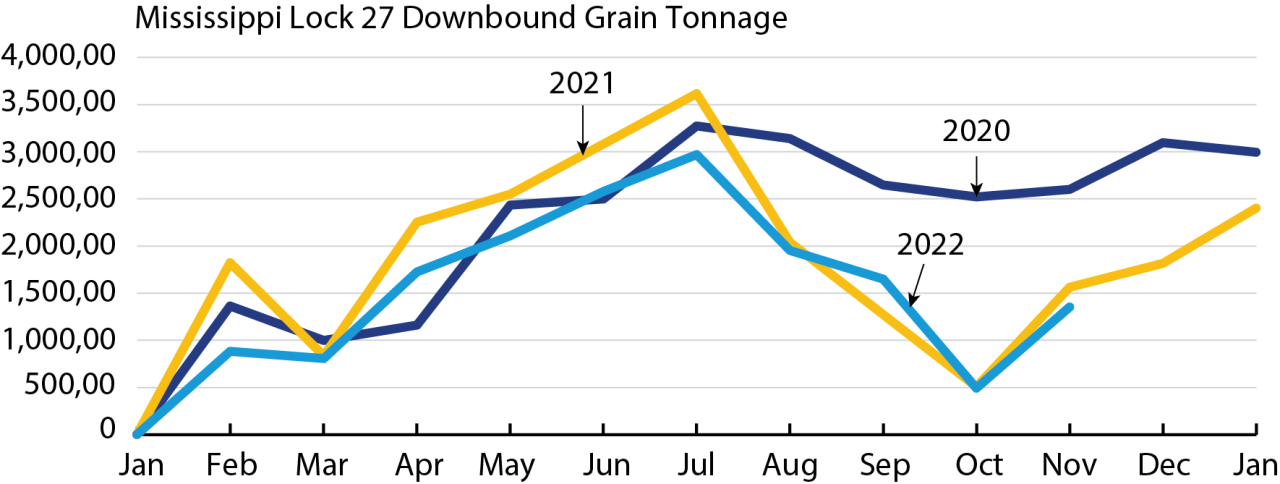

Many major barge commodities such as coal, chemicals, and petroleum move at similar volumes year-round. Grain and other farm products, however, are seasonal. In 2022, downbound (southbound) grain shipments from the Upper Mississippi through Lock 27, the southernmost lock on the river, have followed the 2021 pattern through October (Figure 3), but many of those shipments have been stalled or delayed on the Lower River.

Figure 3: Downbound Barge Grain Shipments

Source: USDA Barge Dashboard

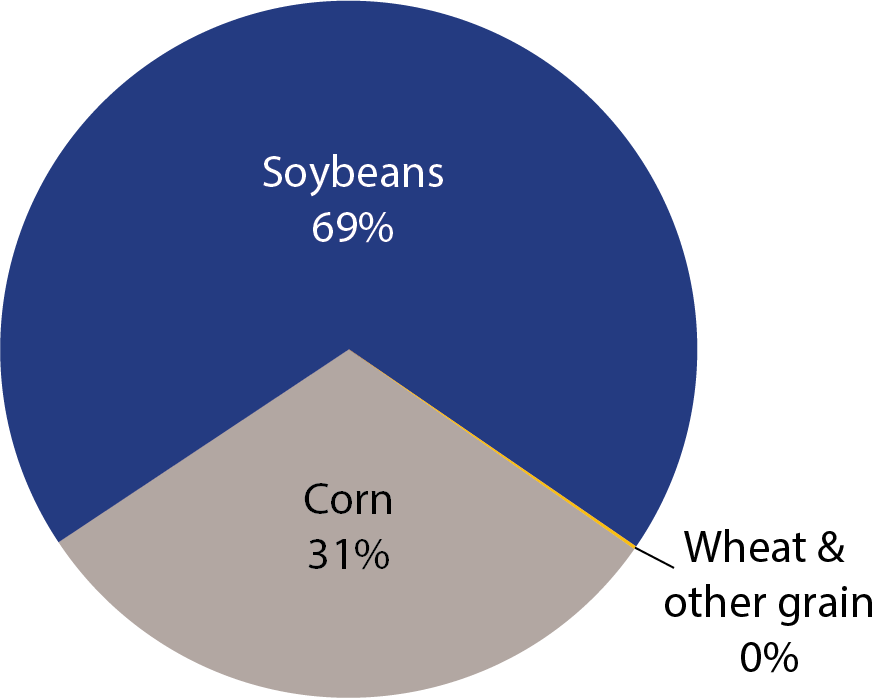

Unfortunately, the low water has coincided with the peak shipping season for U.S. corn and soybeans, our nation’s largest export crops. The October downbound grain and ag product shipments on the Lower Mississippi below Lock and Dam 27 were predominately soybeans and corn, leaving those major export commodities most vulnerable to the Lower River disruption (figure 4).

Figure 4: October 2022 Downbound Grain and Agricultural Product Shares

Source: USDA Barge Dashboard

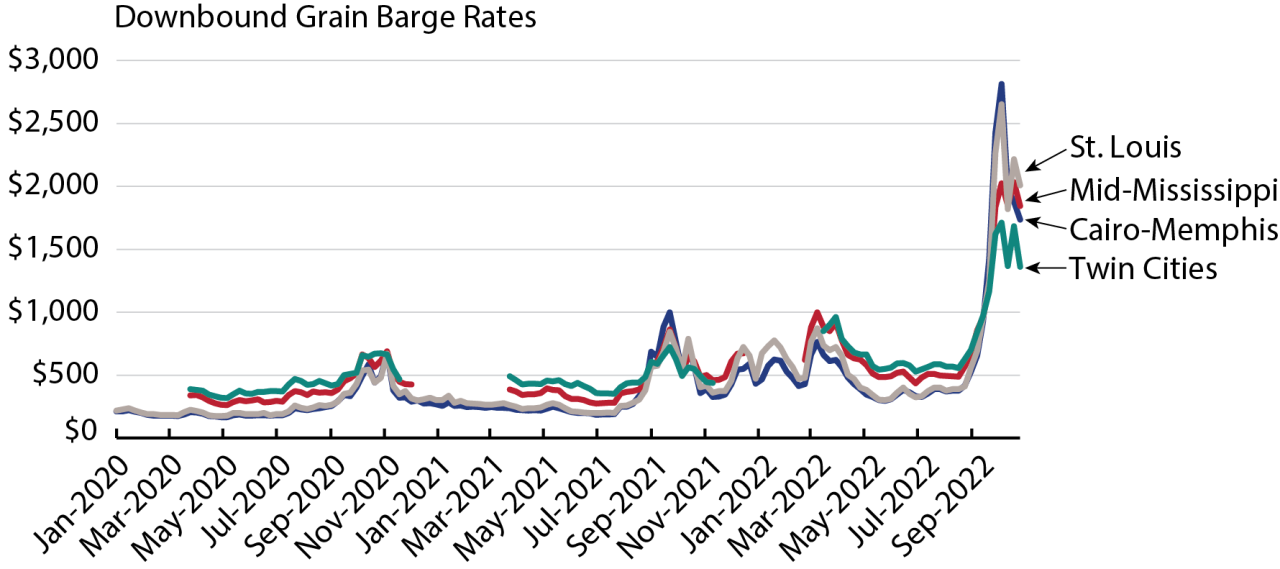

The implications are apparent in barge shipping rates. By early September, barge rates were already at record highs. As Figure 5 shows, downbound grain rates on the Mississippi in October 2022 rose to more than double the 2021 peak and remained very high in early November.

Figure 5: Grain Barge Shipping Rates

Source: USDA Barge Dashboard

Freight shipped on the Mississippi River was already affected by world events.

World demand and prices for grain have been rising due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, drought in other producing areas, and increased consumption in China and elsewhere. Yet, despite the demand, U.S. grain and soybean exports are down due in part to the higher U.S. dollar and in part to the delivery delays caused by the compounded impact of low water and disruption to the supply chain. While domestic grain prices remain low, bid prices for U.S. export corn peaked in mid-October as the river delays were at their worst.

The Soy Transportation Coalition estimates that barge transportation accounts for about 6% of the delivered cost for soybeans shipped from Davenport, Iowa, to Shanghai. As Figure 5 indicates, October barge rates were as much as 400 percent above average, which would raise the delivered price of soybeans by about 24 percent, placing U.S. producers at a cost disadvantage compared to those in Brazil and other competitors.

Grain is not the only commodity affected. The Waterways Council noted that the low water has also delayed coal shipments that are “very much needed in Europe” due to the invasion of Ukraine.

Besides delaying loaded downbound barge tows moving from producing areas to destination ports such as Memphis, South Louisiana, and New Orleans, the low water also delays upbound tows moving fertilizer and cement for spring planting and construction, which also cuts the supply of empty barges for subsequent downbound trips.

1 These include Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, and Missouri along the Mississippi north of its confluence with the Ohio River; Kansas and Nebraska along the navigable portion of the Missouri River; and Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania along the Ohio River.

2 The category of “other agricultural products” excludes cereal grains, live animals and seafood, milled grain, and foodstuffs.